Vorschlag B2

Immigrants

1.

Outline the biographical information given on the author and his parents. (Material 1)

(30 BE)

2.

Analyze how Choudhury’s attitude (Material 1) towards the traditional view of American immigration is conveyed.

(30 BE)

3.

Choose one of the following tasks:

Material 1

3.1

Assess to what extent the cartoon (Material 2) reflects what Choudhury and his family (Material 1) have experienced in the US.

(40 BE)

or

3.2

You are participating in an international school project on identity.

Write an article for the project website in which you discuss the importance of place in shaping one’s identity.

Write an article for the project website in which you discuss the importance of place in shaping one’s identity.

(40 BE)

Kushanava Choudhury: The New World (2017)

This is an excerpt from the introductory chapter of The Epic City, Choudhury’s literary portrait of Calcutta, the city of his birth, from where his family moved to the United States of America.

1

Of all the people who came to Ellis Island in the first decades of the twentieth century,

2

more than half went back. They never told us that on our seventh-grade class trip.

3

The American immigrant myth says that migration is a reset button. The New World

4

offers deliverance from the past, liberation from the Old World’s limited horizons. The

5

myth states: ‘The past is gone. The future awaits. Start over.’

6

It never really works like that. That was the story no one ever told about America. The

7

past is never left behind. It haunts every world you live in. Sometimes it drags you back.

8

By the time I visited Ellis Island on that class trip, I had already migrated halfway

9

around the world four times, flipping back and forth between continents like a dual-voltage

10

appliance. My parents were Indian scientists, torn between nation and vocation. Twice

11

they moved to America, twice they moved back. They were unwilling to leave their country

12

and they were unable to stay. When he was around forty, my father quit his cushy job

13

at a government research institute in Calcutta. He wanted one more chance, he said [...].

14

So, when I was almost twelve, my parents and I moved to Highland Park, New Jersey.

15

Our move carried no Emma Lazarus cadences. We certainly had not arrived tempesttossed,

16

beating at the golden door. Our coming was equivocal, always tied to return. Living

17

in New Jersey, we hardly saw ourselves as immigrants. My parents expected to go back to

18

India, like many of their Bengali friends, someday, eventually. On Saturday nights, they

19

gathered at each other’s homes, ate fourteen-course meals brimming with various types of

20

fish and meat, and derailed each other’s sentences in locomotive Bengali, their conversations

21

full of memories of Calcutta. Return, the duty of return and the dream of return, were

22

spoken of endlessly while eating platefuls of goat curry and hilsa fish. Few, of course,

23

actually went back. There were too many good reasons not to. Nationalism and nostalgia

24

did not pay the bills, raise children or advance careers. And yet that dream of a return to

25

the great metropolis cocooned them like a protective blanket from the alien world all

26

around.

27

As for me – my friends, my neighbourhood, my Calcutta life was gone. In New Jersey,

28

I was in seventh grade in a public school that had almost no Indian students. Cocooning

29

was not an option. I had to fit in fast. I wasn’t assimilating as much as passing. So much

30

of what went on inside my head was from another place. I had happy childhood memories

31

of mid-morning cricket matches during summer vacations, of games played in gullies,

32

rooftops, courtyards and streets. When I moved, it was the streets of the city as much as

33

my childhood that I left behind.

34

We had not had an easy few years in America. The man who had offered the job to my

35

father had made promises he did not keep, and so my father was forced to find other work,

36

work he grew to despise. From time to time, there would be talk of another move, to Georgia,

37

to Colorado, and I would pull down the posters in my room and prepare. We stayed

38

put, the three of us adrift in the treacherous shoals of the lower middle classes, a world of

39

chronic car trouble and clothes from K-Mart. In the fall of my senior year, a piece of good

40

news finally came to our two-bedroom apartment. I had been accepted early to

41

Princeton University .

42

Every immigrant who has lugged worthless foreign degrees through customs knows

43

that where you go to college [...] determines your lot in life. When the acceptance letter

44

from Princeton arrived, my parents acted as if someone had come to our door with balloons

45

and a giant cardboard cheque. It was their happiest day in America. But it wasn’t mine.

46

It is probably universally true that education drives a wedge between us and our hometowns,

47

our families, our earlier selves. But for the immigrant the gap is greater, that divergence

48

in mentality more extreme. My trajectory was taking me farther afield, to Princeton,

49

while a part of me was elsewhere, in another country, in another city. Through all my

50

sojourns I had carried memories on my back like Huien Tsang chair, until at seventeen,

51

I felt hunched over with nostalgia like a middle-aged man. When the Princeton letter arrived,

52

I had what my friend Ben called a ‘premature midlife crisis’.

53

At night, I couldn’t sleep. By day I sleepwalked through classes. Each evening, while

54

my friends assembled at Dunkin’ Donuts, complained about how there was nothing to do

55

in our little town and roared together into the night on long aimless drives, while they

56

enjoyed the languor of spring and that sweet American affliction called senioritis, I stayed

57

home and stewed. In my mind, I hatched a plan. I would go back.

58

India lives in its villages, Mahatma Gandhi had said. So, even though I was a city boy

59

who had never spent a night in an Indian village, I wrote letters back home to arrange to

60

teach in a village school. Instead of Princeton, I would take a year off and head to rural

61

Bengal, I told my parents. But in our two-bedroom apartment full of shared immigrant

62

striving, such a detour was out of the question.

63

Instead I just drove. The black night, the shimmering yellow lines on inviting ribbons

64

of asphalt, the radio jammed loud. Enveloped by night and noise, the mind gave way to a

65

deeper calling. Just drive. It was the mantra of our Jersey youth, an exhortation, a command,

66

an ideology, something hardwired in us as teenage boys. Night after night, I took

67

out my parents’ Toyota and just drove, without destination, without purpose, to escape. [...]

68

After graduating from college, while friends set up their apartments in New York, Boston

69

and Los Angeles, I headed to Calcutta, to join the Statesman.

Source: Choudhury, Kushanava The Epic City. The World on the Streets of Calcutta.”, London: Bloomsbury, 2017, xi –xvi

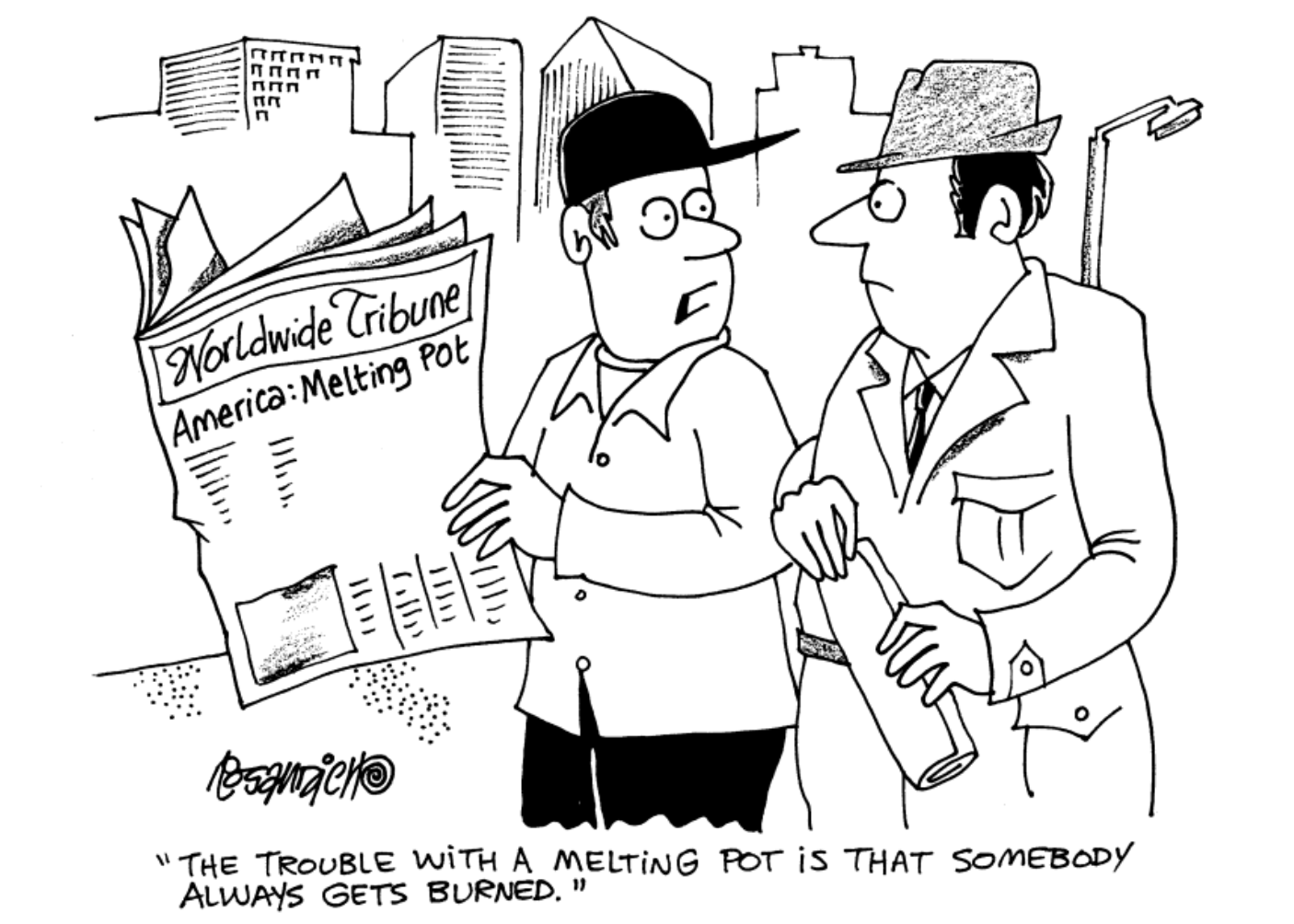

Material 2

Source: Dan Rosandich, cartoonstock

Weiter lernen mit SchulLV-PLUS!

monatlich kündbarSchulLV-PLUS-Vorteile im ÜberblickDu hast bereits einen Account?

Note:

Our solutions are listed in bullet points. In the examination, full marks can only be achieved by writing a continuous text.

Our solutions are listed in bullet points. In the examination, full marks can only be achieved by writing a continuous text.

1.

- In the excerpt from the novel "The Epic City," (2017) author Kushanava Choudhury describes moving between his place of origin, Calcutta, and staying and living in the U.S.

Introduction

- Choudhury's parents were scientists

- they move twice back and forth between India and America

- at the age of 40, his father quit a well-paid government job at a research center in Calcutta

for a new opportunity in New Jersey

- his parents never felt fully immigrated and always had the idea to go back to India one day

- especially when the promised job in New Jersey did not materialize and he had to take a job he began to loathe

- the family's life in the States was marked by financial insecurity

- problems with the car

- cheap clothing

- in constant readiness to return home

- dreams of a return along with memories were cherished by Choudhury's family and him along with their many Bengali friends

Geographic changes of the family

- Choudhury felt he was leaving his childhood behind when he moved to the U.S.

associates happy childhood memories with India

- he had to adjust quickly when he entered an American public school in seventh grade with hardly any Indian classmates

- family could offer him only limited opportunities due to financial worries, so it was a surprise that he was accepted at such a prestigious university as Princeton

- parents were very happy, but Choudhury harbored secret plans to return to India and did not share his parent's joy

- his plan to teach in a Bengali village school was not accepted by his parents

- Choudhury's college years were restless years for him, during which he became estranged from friends, traveled aimlessly, and eventually returned to Calcutta to work for The Statesman, unlike his fellow students

Choudhury's world of emotions

2.

- Ellis Island is the official immigration port of the USA, which the author had already visited as a teenager during a school trip

- however, the American myth does not work as it is always made to believe, there is no "reset button" (l. 3) the past will stay and haunt one for a lifetime (cf. l . 6/7)

- at least in the case of his parents the reset did not work to free them "from the Old World's limited horizons" (l. 4)

- he refutes the myth of a new future and the liberation of the past by telling at the beginning of the excerpt that more than half of the immigrants (cf. l. 2) return to their country of origin

- Choudhury's critical attitude is reinforced by his parents' disappointment and constant plans to return home

- however, the desire to return remains just that - a desire, because "Nationalism and nostalgia did not pay the bills, raise children or advance careers" (l. 23/24)

- parents, however, cling to Bengali culture and friends and celebrate it through evenings out, Bengali food, and memories of home

- the need to stay and the desire to return to India almost tear Choudhury's parents apart

American immigration myth

- "I had already migrated halfway around the world four times." (l. 8/9)

the constant moves weigh on him

- in order to present his own situation to the reader and to illustrate what emotions are triggered in him, Choudhury uses some linguistic devices such as:

- personal experiences

- language with negative connotation

- for him, the American myth is characterized by negativity

- this becomes clear through sentences like "It never really works like that. That was the story no one ever told about America. The past is never left behind." (l. 6/7)

- through allusions that they did not have "an easy few years in America," he refers to the fact that their move to America was not so Emma Lazarus' famous poem promises (cf. l. 15) he also emphasizes "Our move carried no Emma Lazarus cadences."

- by using so many linguistic devices, Choudhurys makes it increasingly clear how much his own experience and the myth are at odds with each other

- he describes the critical financial situation in which his parents find themselves as "treacherous shoals of the lower middle classes" (l. 38)

- he describes himself as "I felt hunched over with nostalgia like a middle-aged man." (l. 51)

- through these descriptions, he emphasizes the difficulty of his parent's situation and his own psychological crisis

- what the myth promises does not materialize for Choudhury is apparent from his parents' persistent desire to return to India and descriptions such as "They were unwilling to leave [...] unable to stay." (l. 11/12)

- the use of statements and descriptions such as "nationalism and nostalgia" (l. 23) and "dream of a return" (l. 24), shows that his family does not feel comfortable in America and longs to return home

- the author has a very doubtful attitude towards the American Dream in general, which he characterizes as a myth, the American values, the so many promises that are empty

- his own experience taught him something quite different and showed him that the American Dream is only wishful thinking

- he feels torn between the two worlds that characterize his homeland and America

- finally, he turns to his homeland and leaves America to work as a journalist in Calcutta

the american myth and Choudhury's experience in contradiction

- all in all, it can be summarized that for Choudhury the American dream is nothing resembling reality

- he underlines this fact by many euphemistic paraphrases

- his own experience as an Indian immigrant is far different from that of the promised myth

Conclusion

3.1

- the cartoon shows two white men of middle age and, judging by their clothing, from different income brackets and skyscraper in the background

- the newspaper whose headline the men are talking about with rather surprised expressions on their faces, is titled - "America: Melting Pot"

- the caption sums up the message: the challenge of a melting pot is that someone is always getting burned

- i.e. in a country where so many immigrants and cultures are united and "merged", there is always someone who will lose something - be it the language or the identity - someone always suffers from it

- this concept leaves immigrants only one choice

to assimilate

- the two men, who do not look like immigrants, and their rather negative attitude emphasize the question raised by the cartoonist, who questions the usefulness of a multicultural society

Introduction and description of the cartoon

- Choudhury's parents, for example, cannot identify at all with the melting pot concept of assimilation

- they have migrated and have no roots anywhere and have a constant desire to return to their homeland

- lack of integration in America - surround themselves with other Indian immigrants (sharing traditional meals and reminiscing about India)

- the author himself, initially adapts to his new home and school and is even accepted to the prestigious Princeton University

- however, he too has nostalgic feelings and eventually develops strong feelings of returning to India as well

Connection between the cartoon's caption and Choudhury's situation

- forces people into a process to become part of the masses

- individuality and cultures are lost and traditions and values are destroyed

- can lead to feelings of inferiority and exclusion

- and lead, as in the case of Choudhury's family, to a constant desire to return home

- the melting pot is the opposite of a welcoming culture, because in such a society, any individual development and freedom to practice one's own culture is "burned"

The downside of the melting pot

- got a place at Princeton

embodies, at least for Choudhury's parents, the fulfillment of the American dream "It was their happiest day in America" (l. 44/45)

- however, the author himself signals that for him it was not the happiest day in America (cf. l. 45)

- he felt like an outsider from an early age - although he tried to fit in, he always lacked a sense of home

- in addition, he had few classmates from his ethnic group

- he could never completely forget India

Contradictions of cartoon and author’s experiences

- in conclusion, the fulfillment of the American Dream requires a willingness to leave the past behind and to embrace new ideas and culture

- especially for ethnic groups with strong ties to old Indian traditions like the author's family, this is not always possible

- James T. Adams coined the term "melting pot" and describes America as a country where everyone, regardless of origin, religion or income level, has the chance to realize their potential and lead a better and richer life

- in the years that followed, other ideas for the integration of immigrants were developed and established

in which immigrants are integrated in such a way that they retain their "identity" and culture and do not force anyone to adapt to the majority society

Conclusion

3.2

- integration into the USA is very difficult for many young immigrants

no matter how hard they try

- the prejudiced country that promises so much with the American dream expects these people to assimilate and forget their past

- this makes them feel rejected and makes them long for their homeland

- according to new research, origin has a greater influence on identity formation than the majority society

Challenges of integrating into the USA

- what has been particularly observed is the importance of the place of origin for in identity formation among second- and even third-generation immigrants in the U.S. and the U.K.

- young people often live the traditions, values and religions of their parents place of origin

- in his autobiography, author Kushanava Choudhury recounts his willingness as a teenager to leave India and live the American life

- after graduation, however, he decided to leave the U.S. again

to work as a journalist in his home country of Calcutta

- his decision to leave the U.S. and presitigous Princeton University to return home was initially hindered and opposed by his parents

- they supported his life and career opportunities in the USA

- he, on the other hand, was haunted by nostalgic childhood memories and gradually withdrew from his fellow students and friends, until he finally left the USA

Formation of identity:

Choudhury's experience

Choudhury's experience

- the relationship of people to a place can be very emotional and life-long formative - as also Choudhury' example shows

- especially the identity of young people is shaped by places

it conveys a feeling of belonging and familiarity

- feelings that are difficult to forget later

- there is an interaction between people and their environment - people identify with it and the environment is in turn shaped by them

- behavior and attitude towards life will also be influenced by places - e.g. conservative behavior in more rural areas and open and diverse behavior in cities

Connection between a place and one's identity

- however, there are also arguments in our global world against the importance of a place

globalization

- globalization and being used to international travel from a young age changes the sense and meaning for and of a particular place

- people who move frequently also have a weaker connection to a place

- sayings like "home is not a place but where the friends are" - underlines that places lose or get a different meaning

Counterarguments for the importance of place

- ultimately, it can be summarized that place is still of great importance for identity formation

especially in the case of involuntary migration (as a result of war, poverty or even oppression in the home country)

- people who have had to leave their home country because of this suffer particularly from loneliness and loss

- all in all, however, it can still be said that in today's fast-paced world dominated by the Internet, place is gradually losing its significance

Conclusion