Task 1

Working on the text

Do the following tasks, writing coherent Texts. Use your own words as far as appropriate.

1.

Summarise the author's suggestions for tackling the issue of inequality in current climate policy.

2.

Analyse how structure and language support the author's opinion.

28 BE

Writing

3.

Choose one of the following tasks:

3.1

"To accelerate the energy transition, we must also think outside the box." (l.56)

Taking the quotation from the text as a starting point, comment on different ways to meet this challenge.

or

Taking the quotation from the text as a starting point, comment on different ways to meet this challenge.

3.2

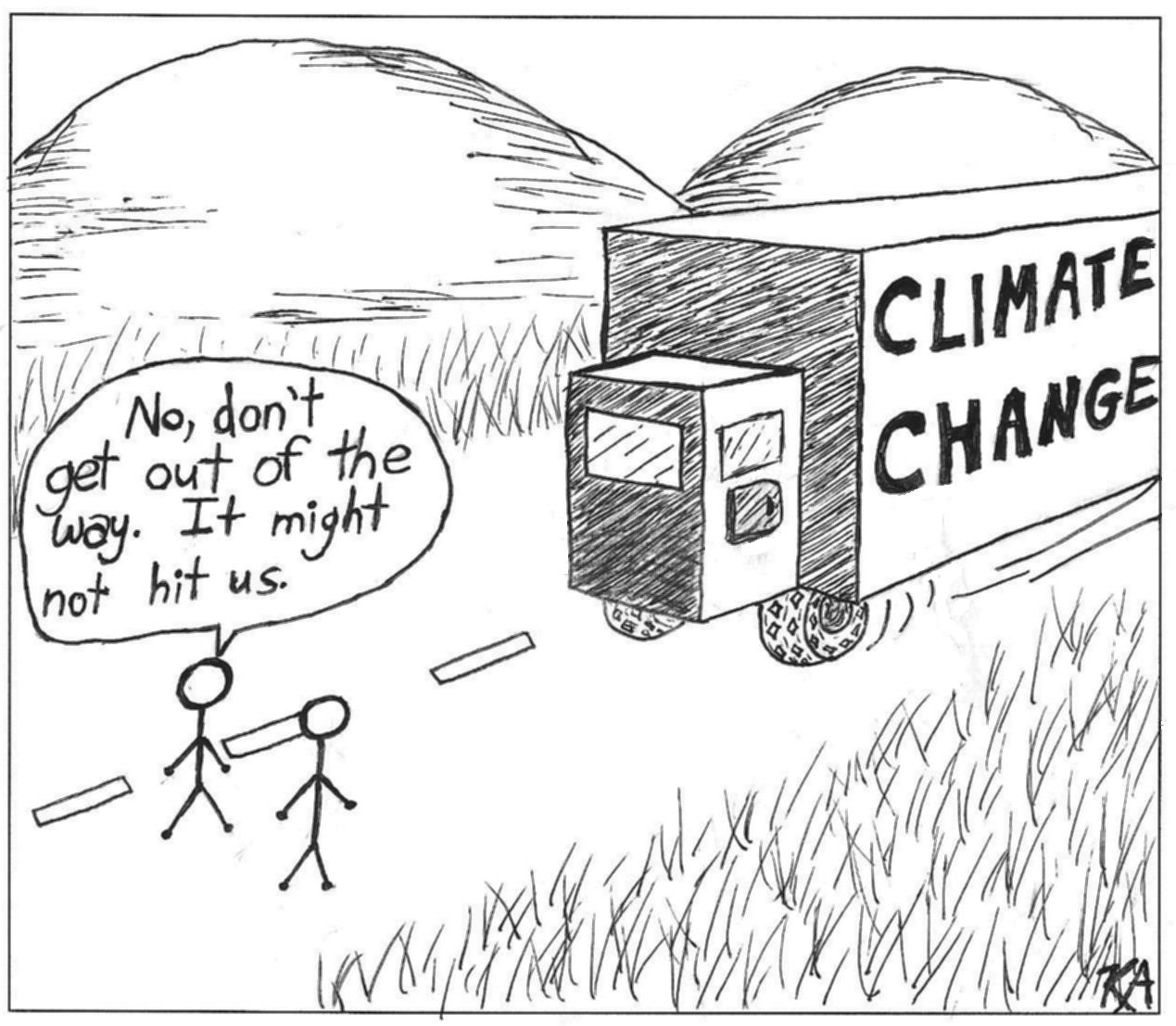

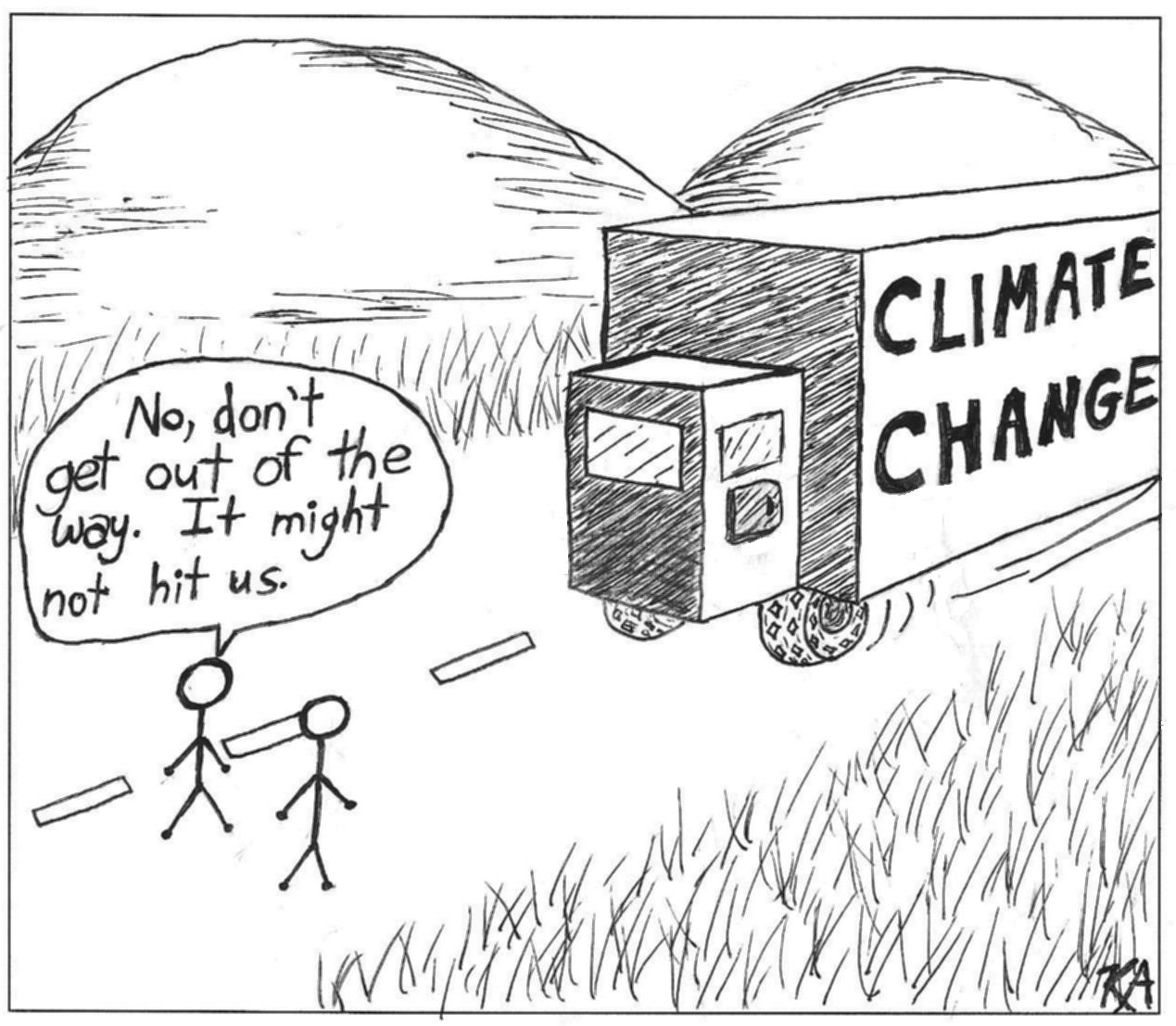

Using the message of the cartoon as a starting point, evaluate the impact of climate change on our generation.

http://1.bp.blogspot.com/-z-1R_VJHcCg/UfDeSDWYegI/AAAAAAAAEmA/ffNbLq0kpoQ/s1600/cartoon1.jpg (22.05.2023)

32 BE

The richest 10% produce about half of greenhouse gas emissions. They should pay to fix the climate.

1

Let's face it: our chances of staying under a 2 °C increase in global temperature are not looking

2

good. If we continue business as usual, the world is on track to heat up by 3 °C at least by the

3

end of this century. At current global emissions rates, the carbon budget that we have left if we

4

are to stay under 1.5 °C will be depleted in six years. The paradox is that, globally, popular

5

support for climate action has never been so strong. According to a recent United Nations poll,

6

the vast majority of people around the world sees climate change as a global emergency. So,

7

what have we got wrong so far?

8

There is a fundamental problem in contemporary discussion of climate policy: it rarely

9

acknowledges inequality. Poorer households, which are low CO2 emitters, rightly anticipate

10

that climate policies will limit their purchasing power. In return, policymakers fear a political

11

backlash should they demand faster climate action. The problem with this vicious circle is that

12

it has lost us a lot of time. The good news is that we can end it.

13

Let's first look at the facts: 10% of the world's population are responsible for about half of all

14

greenhouse gas emissions, while the bottom half of the world contributes just 12% of all

15

emissions. This is not simply a rich versus poor countries divide: there are huge emitters in poor

16

countries, and low emitters in rich countries. Consider the US, for instance. Every year, the

17

poorest 50% of the US population emit about 10 tonnes of CO2 per person, while the richest

18

10% emit 75 tonnes per person. That is a gap of more than seven to one. [...]

19

Where do these large inequalities come from? The rich emit more carbon through the goods

20

and services they buy, as well as from the investments they make. Low-income groups emit

21

carbon when they use their cars or heat their homes, but their indirect emissions - that is, the

22

emissions from the stuff they buy and the investments they make - are significantly lower than

23

those of the rich. The poorest half of the population barely owns any wealth, meaning that it

24

has little or no responsibility for emissions associated with investment decisions.

25

Why do these inequalities matter? After all, shouldn't we all reduce our emissions? Yes, we

26

should, but obviously some groups will have to make a greater effort than others. Intuitively,

27

we might think here of the big emitters, the rich, right? True, and also poorer people have less

28

capacity to decarbonize their consumption. It follows that the rich should contribute the most

29

to curbing emissions, and the poor be given the capacity to cope with the transition to 1.5 °C or

30

2 °C. Unfortunately, this is not what is happening - if anything, what is happening is closer to

31

the opposite.

32

It was evident in France in 2018, when the government raised carbon taxes in a way that hit

33

rural, low-income households particularly hard, without much affecting the consumption habits

34

and investment portfolios of the well-off. Many families had no way to reduce their energy

35

consumption. They had no option but to drive their cars to go to work and to pay the higher

36

carbon tax. At the same time, the aviation fuel used by the rich to fly from Paris to the French

37

Riviera was exempted from the tax change. Reactions to this unequal treatment eventually led

38

to the reform being abandoned. These politics of climate action, which demand no significant

39

effort from the rich yet hurt the poor, are not specific to any one country. Fears of job losses in

40

certain industries are regularly used by business groups as an argument to slow climate policies.

41

Countries have announced plans to cut their emissions significantly by 2030 and most have

42

established plans to reach net-zero somewhere around 2050. Let's focus on the first milestone,

43

the 2030 emission reduction target: according to my recent study, as expressed in per capita

44

terms, the poorest half of the population in the US and most European countries have already

45

reached or almost reached the target. This is not the case at all for the middle classes and the

46

wealthy, who are well above - that is to say, behind - the target.

47

One way to reduce carbon inequalities is to establish individual carbon rights, similar to the

48

schemes that some countries use to manage scarce environmental resources such as water. Such

49

an approach would inevitably raise technical and information issues, but it is a strategy that

50

deserves attention. There are many ways to reduce the overall emissions of a country, but the

51

bottom line is that anything but a strictly egalitarian strategy inevitably means demanding

52

greater climate mitigation effort from those who are already at the target level, and less from

53

those who are well above it; this is basic arithmetic. Arguably, any deviation from an egalitarian

54

strategy would justify serious redistribution from the wealthy to the worse off to compensate

55

the latter. [...]

56

To accelerate the energy transition, we must also think outside the box. Consider, for example,

57

a progressive tax on wealth, with a pollution top-up. This would accelerate the shift out of fossil

58

fuels by making access to capital more expensive for the fossil fuel industries. It would also

59

generate potentially large revenues for governments that they could invest in green industries

60

and innovation. Such taxes would be politically easier to pass than a standard carbon tax, since

61

they target a fraction of the population, not the majority. At the world level, a modest wealth

62

tax on multimillionaires with a pollution top-up could generate 1.7% of global income. This

63

could fund the bulk of extra investments required every year to meet climate mitigation efforts.

64

Whatever the path chosen by societies to accelerate the transition - and there are many potential

65

paths - it's time for us to acknowledge there can be no deep decarbonization without profound

66

redistribution of income and wealth.

Chancel, Lucas: The richest 10% produce about half of greenhouse gas emissions. They should pay to fix the climate. In:, The Guardian. 8th December 2021, https://www.theguardian.com (14.03.2022)

Weiter lernen mit SchulLV-PLUS!

monatlich kündbarSchulLV-PLUS-Vorteile im ÜberblickDu hast bereits einen Account?

Note:

Our solutions are listed in bullet points. In the examination, full marks can only be achieved by writing a continuous text. It must be noted that our conclusions contain only some of the possible aspects. Students can also find a different approach to argumentation.

Our solutions are listed in bullet points. In the examination, full marks can only be achieved by writing a continuous text. It must be noted that our conclusions contain only some of the possible aspects. Students can also find a different approach to argumentation.

1.

In the article "The richest 10% produce about half of greenhouse gas emissions. They should pay to fix the climate." written by Lucas Chancel, published 2022 in The Guardian, the author suggests several ways to address the issue of inequality in current climate policy.

Introduction

- it is justifiable for lower-income households to anticipate that climate policies will reduce their ability to make purchases

- despite emitting less CO2, individuals in poverty are disproportionately impacted compared to those who are financially well-off

- the least affluent 50% of the population carry minimal or no responsibility for emissions linked to investment choices.

- in both the United States and several European countries, the lower-income segment of society has already achieved the emission reduction targets, while the middle-class and upper-class citizens are falling short

- the implementation of individual carbon rights based on individual CO2 emissions, which promotes an egalitarian approach

- introducing a progressive tax on wealth along with additional pollution charges, with the generated revenues directed towards investments in environmental protection

- overall, the author advocates for a significant redistribution of income and wealth as a means to tackle the climate crisis

Main Body

The author's point of view

The author's point of view

2.

Through the use of language, stylistic devices, and the structural composition of the text, the author Lucas Chancel, tackles the matter of the climate crisis and the accompanying inequality, with the intention of increasing awareness, engaging the readership, and fostering critical thinking.

Introduction

- the writer employs attention-grabbing titles and presents a paradox in order to captivate the reader's interest and compel them to continue reading

- in the main section, the author initially presents their perspective on the matter, supporting it with explanations and illustrations

- finally, in the concluding part, the author offers solutions to address the problem and urges the audience to take action

- employing a well-defined structure to articulate their viewpoint aids in comprehending the issue at hand

Main Body

structure of the text

structure of the text

- chancel employs imperative language to urge the reader to be attentive and bring about a greater understanding of the subject matter, exemplified by phrases such as "let's face it" and "consider, for example"

- by employing inclusive pronouns such as "we," "let's," and "time for us," (l. 65) Chancel directly engages the reader and establishes a connection between the reader and the author

- this approach aims to foster unity and cooperation in addressing the topic at hand

language

addressing the reader

addressing the reader

- in lines 25 and 26, the author employs rhetorical questions such as "Why do these inequalities matter? After all, shouldn't we all reduce our emissions?" to effectively draw attention to the issue and raise awareness

- to reinforce their perspective, the author proceeds to answer these rhetorical questions in the subsequent sentence, as evidenced by the statement "... the rich, right? True, and ..." (l. 26/27)

- with the metaphor "think outside the box," the author aims to encourage readers to engage in critical thinking and prompt them to break away from familiar patterns and reconsider their behaviors

rethorical question and metaphor

- through the consistent utilization of contrasting elements, such as "rich versus poor" (l. 15) or "huge emitters in poor countries, and low emitters in rich countries" (l. 15/16) the author effectively portrays and emphasizes the disparity in carbon dioxide emissions and the consequent burden borne by different parties

contrasts

- furthermore, the writer employs a blend of casual and formal language

- he incorporates aspects of spoken communication such as the use of phrases like ",right?" (l. 27) and interjections like "above - that is to say, behind - the target." (l. 46)

- additionally, the author utilizes a colloquial selection of words such as "stuff" (l. 22) and "Let's face it." (l. 1) to bridge the gap between himself and the reader

- by adopting an informal style, Chancel aims to enhance the accessibility of the subject matter and establish a sense of social closeness

- the formal language of the author forms a strong contrast to the almost colloquial language he uses in between and strengthens the authenticity and credibility of Chancel

formal and informal language

Ultimately, it can be argued that the language and structure of the text effectively support the author's opinion and raise awareness about the issue of climate crises and the growing inequality associated with attempts to address them.

Conclusion

3.1

Building upon the quote from Lucas Chancel's text, "The richest 10% produce about half of greenhouse gas emissions. They should pay to fix the climate," there are various approaches to address this challenge of accelerating the energy transition and addressing climate change. Today, in order to accelerate the energy transition and mitigate the risks of the climate crisis, it is crucial for humanity to overcome entrenched social behavioral patterns and embrace innovative and unconventional thinking. Breaking free from established norms and thinking "out of the box" becomes an essential challenge we must confront.

Introduction

- energy transition refers to the process of shifting from fossil fuel-based energy sources, such as coal, oil, and natural gas, to cleaner and more sustainable alternatives

- it involves transitioning towards renewable energy sources like solar, wind, hydro, and geothermal power, as well as increasing energy efficiency and adopting innovative technologies

- the goal of the energy transition is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, mitigate climate change, enhance energy security, and promote a more sustainable and resilient energy system

Main Body

Energy transition

Energy transition

- encouraging sustainable practices at an individual and societal level can play a significant role

- promoting awareness about the impacts of personal choices, encouraging energy-saving habits, and fostering a culture of sustainability can lead to more responsible energy consumption patterns

- it is essential for individuals to engage in self-reflection regarding their lifestyles, encompassing areas such as exploring alternative modes of transportation, considering sustainable practices within the fashion industry, reevaluating energy consumption habits, and reassessing personal expectations

- the fashion industry's impact on the environment is significant, and people should reflect on their consumption habits and consider sustainable alternatives

- rethinking personal expectations is also vital

- society often promotes excessive consumption and a "more is better" mentality, which can lead to unnecessary waste and resource depletion

Social awareness and change of behavior

- mobilizing financial resources towards sustainable projects is vital for accelerating the energy transition

- governments, businesses, and financial institutions should prioritize investing in renewable energy and green infrastructure, while divesting from fossil fuel industries

- Implementing carbon pricing mechanisms and providing incentives for sustainable investments can drive the necessary capital flow

Green finance and investments

- transitioning from fossil fuel-powered vehicles to electric vehicles (EVs) is an effective way to reduce emissions from the transportation sector

- supporting the development of EV infrastructure, incentivizing EV adoption, and promoting research on sustainable alternatives like hydrogen fuel cells can accelerate this transition

Transportation

- climate change is a global challenge that requires international cooperation

- encouraging collaboration among nations, particularly in terms of technology transfer and financial support, can help ensure a more equitable distribution of resources and efforts to combat climate change

International Cooperation

In summary, individuals play a crucial role in driving the energy transition. By reflecting on and altering lifestyles, including transportation choices, fashion preferences, energy consumption patterns, and personal expectations, people can actively contribute to a more sustainable and environmentally conscious future

Conclusion

3.2

- the cartoon conveys a thought-provoking message about the impact of climate change on our generation

- it symbolises the dangerous complacency and lack of urgency that often characterises our response to this global crisis

- as we assess the impact of climate change on our generation, we can understand the seriousness of the situation and the urgent need for action

- by depicting the truck labeled "Climate Change" approaching the figures in the street, it symbolizes the urgent and impending threat that climate change poses to our lives and the world we inhabit

- however, the figure's response expressing indifference and a lack of action, reflects a dangerous mindset that undermines the gravity of the situation

Introduction

description of the cartoon and its message

description of the cartoon and its message

- climate change is an existential crisis that affects every aspect of our lives

- its impacts are already being felt globally, with rising temperatures, extreme weather events, sea-level rise, and ecosystem disruptions becoming increasingly frequent and severe

- these effects have wide-ranging consequences, including threats to human health, food security, water resources, and economic stability

- our generation is particularly vulnerable to the long-term consequences of climate change

- while we are witnessing the early stages of its effects, future generations will bear the brunt of the damage if we fail to take decisive action

- the choices we make now will determine the trajectory of our planet and the quality of life for future generations

effects of climate change and relevance for the young generation

- climate change exacerbates inequalities, as marginalized communities are disproportionately affected

- vulnerable populations, including those living in poverty, indigenous communities, and developing nations, bear the brunt of climate-related disasters due to limited resources, inadequate infrastructure, and fewer means to adapt

- the cartoon's message highlights a lack of urgency that affects our ability to effectively address climate change

- it reflects a mentality that ignores the severity of the problem and disregards the need for immediate action

- to address climate change, we need to recognise its severity, prioritise sustainability and work together to mitigate its impacts

- a shift in thinking is needed in our society, away from material consumerism and towards a frugal and sustainable lifestyle

social aspects

- economically and politically, climate change presents risks and opportunities and requires action by all

- on the one hand, it leads to job losses in sectors that are e.g. heavily dependent on fossil fuels

- while at the same time it promotes the growth of renewable energies and innovative industries and drives companies to implement sustainable production processes

- the threat of rising prices is omnipresent

- the costs of adapting to and mitigating climate change are significant, and failure to act in time can have long-term economic consequences

- disruptions caused by climate-related disasters can lead to social unrest, displacement, and conflicts over resources

- it also highlights the need for international cooperation, as climate change transcends national boundaries and requires collective action to mitigate its effects

economical and political aspects

Overall, the impact of climate change on our generation is profound and far-reaching. It threatens our environment, health, economy, and social fabric. The cartoon's message serves as a reminder that ignoring the imminent dangers of climate change is a reckless approach. We must take immediate action to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions, transition to renewable energy sources, adopt sustainable practices, and promote climate resilience. By doing so, we can secure a better future for ourselves and future generations, ensuring a safer and more sustainable planet.

Conclusion